Dignity and Redemption: A Close Reading of "The Lonely Man of Faith"

There are two levels of dignity and redemption in "The Lonely Man of Faith"

This post is just about a point I noticed in The Lonely Man of Faith recently, thanks to an ongoing dialogue about the book with a former student, Mikey Lerman. If you’re not interested in a close reading of The Lonely Man of Faith, maybe come back for the next post.

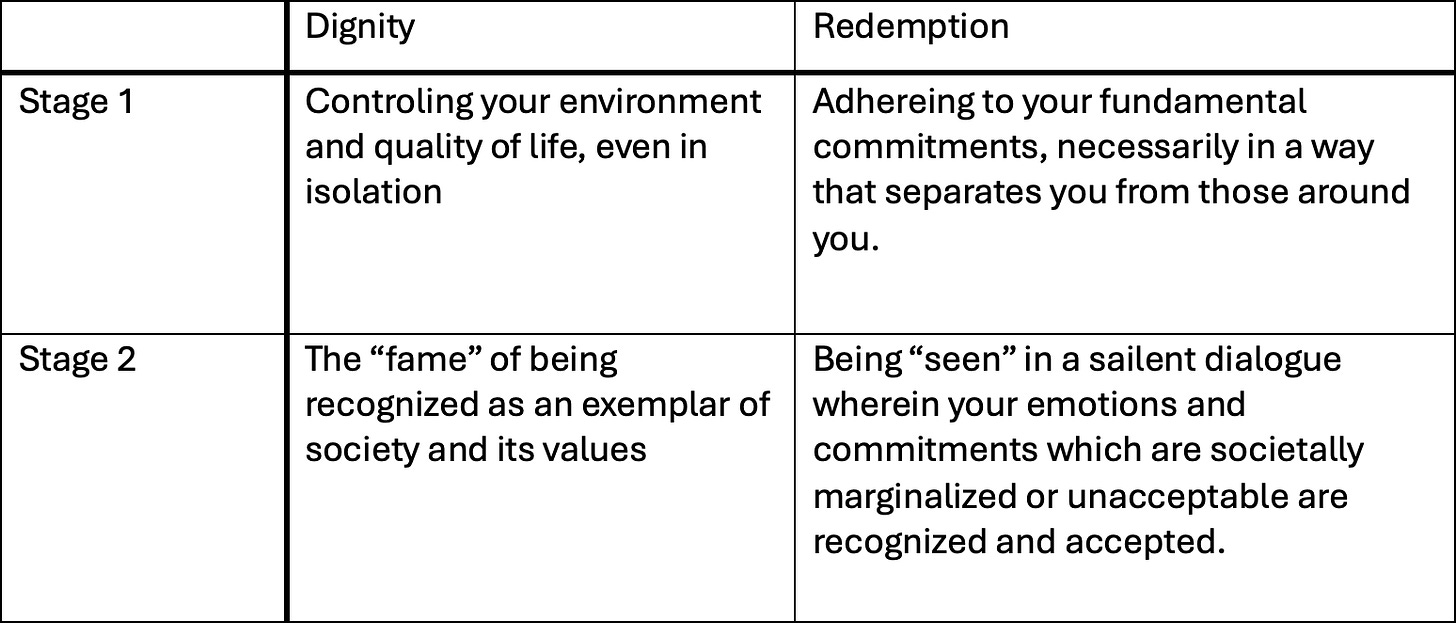

The book is structured around binary ideas, all arranged along the Adam the first/Adam the second binary. In this post, the one that concerns me is “Dignity” vs. “Redemption.” While not stating it directly, Rav Soloveitchik is fairly explicit that redemption is a two-stage process, but I’ve recently come to realizes that not only is dignity also composed of two stages, they parallel the two stages of redemption.

While it comes second in the book, redemption is more explicit, so I’ll start with that.

Redemption

The first stage of redemption, what Rav Soloveitchik calls “cathartic redemptiveness,” is explicitly contrasted with dignity.

There are two basic distinctions between dignity and cathartic redemptiveness:

1. Being redeemed is, unlike being dignified, an ontological awareness. It is not just an extraneous, accidental attribute - among other attributes - of being, but a definitive mode of being itself. A redeemed existence is intrinsically different from an unredeemed. Redemptiveness does not have to be acted out vis-a-vis the outside world. Even a hermit, while not having the opportunity to manifest dignity, can live a redeemed life. Cathartic redemptiveness is experienced in the privacy of one's in-depth personality, and it cuts below the relationship between the "I" and the "thou" (to use an existentialist term) and reaches into the very hidden strata of the isolated "I" who knows himself as a singular being. When objectified in personal and emotional categories, cathartic redemptiveness expresses itself in the feeling of axiological security. The individual intuits his existence as worthwhile, legitimate, and adequate, anchored in something stable and unchangeable.

2. Cathartic redemptiveness, in contrast to dignity, cannot be attained through man's acquisition of control of his environment, but through man's exercise of control over himself. A redeemed life is ipso facto a disciplined life. While a dignified existence is attained by majestic man who courageously surges forward and confronts mute nature - a lower form of being- in a mood of defiance, redemption is achieved when humble man makes a movement of recoil, and lets himself be confronted and defeated by a Higher and Truer Being. God summoned Adam the first to advance steadily, Adam the second to retreat. Adam the first He told to exercise mastery and to "fill the earth and subdue it," Adam the second, to serve. He was placed in the Garden of Eden "to cultivate it and to keep it." (LMOF, Maggid 2018, 29–30)

Redemption is, in its first stage, almost antisocial. It undercuts “the relationship between the ‘I’ and the ‘thou’” (and here you can hear Rav Soloveitchik’s engagement with Buber). Cathartic redemptiveness is something a person can attain in isolation, by living a disciplined life guided by faith/their values/etc. The person attaining this level of redemption believes in certain things, they have certain “fundamental commitments” in the language of LMOF, ch. 9, and they choose to live according to them rather than merely based on rational, utilitarian calculus.

The second stage of redemption, in contrast, is specifically attained through a social relationship:

[I]f Adam is to bring his quest for redemption to full realization, he must initiate action leading to the discovery of a companion who, even though as unique and singular as he, will master the art of communicating and, with him, form a community. However, this action, since it is part of the redemptive gesture, must also be sacrificial. The medium of attaining full redemption is, again, defeat. This new companionship is not attained through conquest, but through surrender and retreat. “And the eternal God caused an overpowering sleep to fall upon the man” (Gen. 2:21). Adam was overpowered and defeated—and in defeat he found his companion. (LMOF, 32–33)

If God had not joined the community of Adam and Eve, they would have never been able and would have never cared to make the paradoxical leap over the gap, indeed abyss, separating two individuals whose personal experiential messages are written in a private code undecipherable by anyone else. Without the covenantal experience of the prophetic or prayerful colloquy, Adam absconditus would have persisted in his he-role and Eve abscondita in her she-role, unknown to and distant from each other. Only when God emerged from the transcendent darkness of He-anonymity into the illumined spaces of community knowability and charged man with an ethical and moral mission, did Adam absconditus and Eve abscondita, while revealing themselves to God in prayer and in unqualified commitment, also reveal themselves to each other in sympathy and love on the one hand and in common action on the other. Thus, the final objective of the human quest for redemption was attained; the individual felt relieved from loneliness and isolation. The community of the committed became, ipso facto, a community of friends—not of neighbors or acquaintances. Friendship—not as a social surface-relation but as an existential in-depth-relation between two individuals—is realizable only within the framework of the covenantal community, where in-depth personalities relate themselves to each other ontologically and total commitment to God and fellow man is the order of the day. (LMOF, 57; emphasis added)

The dialogic relationship is the peak of redemption in LMOF. This is not a relationship wherein two people speak to and learn about one another. It is a “sacrificial” act wherein each person opens up to the other without imposing their own understanding upon the other. It is not a rational process, it is essentially about silent listening and acceptance of the other as they present themselves (fully explaining this would require a much longer exploration of dialogue in LMOF; for a key paragraph, see the addendum below). The second stage of redemption is when every person can be “seen” and accepted within a social framework, whether just on the one-to-one level or on level of “the covenantal community.”

Dignity

As we will see, dignity follows the same basic structure. The first stage of dignity is about the capacity to improve one’s life, independent of any social factor.

[M]an is a dignified being and to be human means to live with dignity... Man acquires dignity through glory, through his majestic posture vis-a-vis his environment.

The brute’s existence is an undignified one because it is a helpless existence. Human existence is a dignified one because it is a glorious, majestic, powerful existence. Hence, dignity is unobtainable as long as man has not reclaimed himself from coexistence with nature and has not risen from a non-reflective, degradingly helpless instinctive life to an intelligent, planned, and majestic one. (LMOF, 11–12)

Man of old who could not fight disease and succumbed in multitudes to yellow fever or any other plague with degrading helplessness could not lay claim to dignity. Only the man who builds hospitals, discovers therapeutic techniques, and saves lives is blessed with dignity. Man of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries who needed several days to travel from Boston to New York was less dignified than modern man who attempts to conquer space, boards a plane at the New York airport at midnight and takes several hours later a leisurely walk along 1he streets of London. (LMOF, 13)

This stage of dignity is simply about quality of life and, more importantly, control over that quality. To be dignified, on this account, is to be able to relieve your own suffering, and to have done so.

However, there is a second stage, because for Rav Soloveitchik, “dignity” is inherently a social term.

Dignity is a social and behavioral category, expressing not an intrinsic existential quality but a technique of living, a way of impressing society, the know-how of commanding respect and attention of the other fellow, a capacity to make one's presence felt. In Hebrew, the noun kavod, dignity, and the noun koved, weight, gravitas, stem from the same root. The man of dignity is a weighty person. The people who surround him feel his impact. Hence, dignity is measured not by the inner worth of the in-depth personality, but by the accomplishments of the surface personality. No matter how fine, noble, and gifted one may be, he cannot command respect or be appreciated by others if he has not succeeded in realizing his talents and communicating his message to society through the medium of the creative majestic gesture... Dignity is linked with fame. There is no dignity in anonymity. If one succeeds in putting his message across, he may lay claim to dignity. The silent person, whose message remains hidden and suppressed in the in-depth personality, cannot be considered dignified. (LMOF, 20–21)

As in the second stage of redemption, the second stage of dignity is inherently social. To be dignified, at this point, is not simply to relieve your own suffering or improve your quality of life, but to be seen doing so. Such a person is evaluated on the same standard as everyone else, and they emerge as superior (in contrast to the second stage of redemption, wherein the individuals cannot be compared to one another, and to be redeemed is to be seen in your singularity).

To sum up, here it is as a table:

Addendum: Key excerpt on dialogue in The Lonely Man of Faith:

In the natural community which knows no prayer, majestic Adam can offer only his accomplishments, not himself. There is certainly even within the framework of the natural community, as the existentialists are wont to say, a dialogue between the “I” and the “thou.” However, this dialogue may only gratify the necessity for communication which urges Adam the first to relate himself to others, since communication for him means information about the surface activity of practical man. Such a dialogue certainly cannot quench the burning thirst for communication in depth of Adam the second, who always will remain a homo absconditus if the majestic logoi of Adam the first should serve as the only medium of expression. What really can this dialogue reveal of the numinous in-depth personality? Nothing! Yes, words are spoken, but these words reflect not the unique and intimate, but the universal and public in man. As homo absconditus, Adam the second is not capable of telling his personal experiential story in majestic formal terms. His emotional life is inseparable from his unique modus existentiae and therefore, if communicated to the “thou” only as a piece of surface information, unintelligible. This story belongs exclusively to Adam the second, it is his and only his, and it would make no sense if disclosed to others... Distress and bliss, joys and frustrations are incommunicable within the framework of the natural dialogue consisting of common words. By the time homo absconditus manages to deliver the message, the personal and intimate content of the latter is already recast in the lingual matrix, which standardizes the unique and universalizes the individual. (LMOF, 56–57)